The First Sprinkler Save: How an 1877 Mill Fire Proved the Power of Automatic Sprinklers

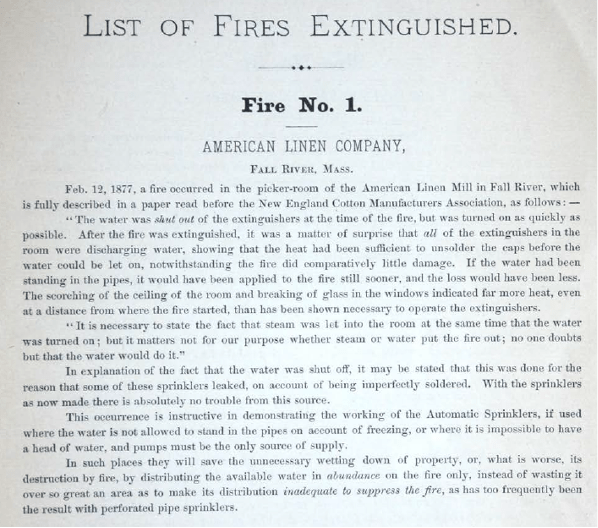

On February 12, 1877, a fire broke out in the picker room of the American Linen Company mill in Fall River, Massachusetts. While the incident caused relatively minor damage, it would go on to secure a permanent place in fire protection history.

This event is widely recognized as the first documented instance of an automatic sprinkler system extinguishing a fire.

The building was protected by a Parmelee Automatic Sprinkler, a pioneering technology developed in the 19th century and manufactured by Frederick Grinnell. The system operated exactly as its inventor intended—activating automatically in response to heat and controlling the fire at its earliest stage.

Technology Born of Necessity

The concept of the automatic sprinkler dates to the early 1800s, but its first known US installation occurred in a piano factory in New Haven, Connecticut. The factory was owned by Henry Parmelee, who sought a better way to protect his property from fire.

Parmelee partnered with Frederick Grinnell, a regional manufacturer of fire protection equipment, to refine and produce the first practical automatic sprinkler. Their collaboration laid the groundwork for a technology that would ultimately save countless lives and protect billions of dollars in property worldwide.

How the Early Parmelee Sprinkler Worked

The original Parmelee sprinkler was elegantly simple and mechanically reliable:

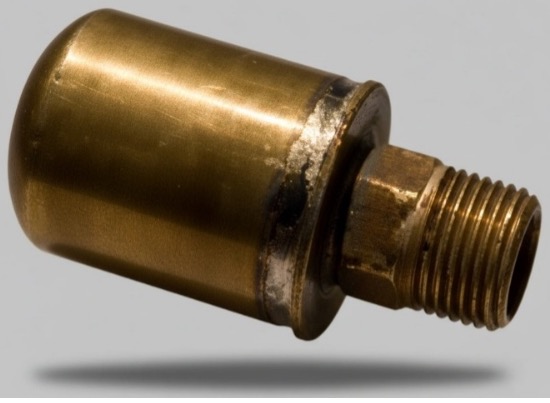

- A brass or bronze cylindrical body, threaded for connection to water piping

- Small perforated holes at one end for water discharge

- A metallic cap held in place by solder, engineered to melt at a specific temperature

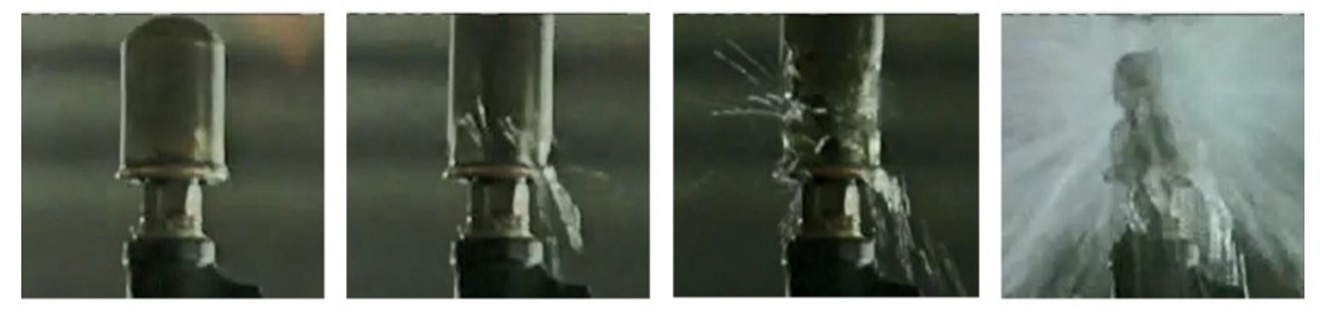

When exposed to heat from a fire, the solder melted, releasing the cap. Water pressure within the pipe then forced the cap away, allowing water to discharge directly onto the fire through the perforations in the sprinkler body.

No detection system. No human intervention. Just heat, physics, and water—working together automatically.

Proof in Practice: The 1877 Mill Fire

In the Fall River fire, the heat was sufficient to activate multiple sprinklers in the room. Although the water supply had initially been shut off due to concerns about leaking soldered caps—an issue later resolved through improved manufacturing—the sprinklers discharged once water was restored, quickly and effectively controlling the fire.

Contemporary accounts noted that the fire produced significant heat, scorching ceilings and breaking windows, yet the damage remained limited. The incident demonstrated a principle that still defines sprinkler protection today—early intervention limits consequences by controlling fires before they escalate into catastrophic losses.

A Legacy That Endures

Nearly 150 years later, the fundamentals proven in that 1877 mill fire remain unchanged. Automatic sprinklers remain the most effective means of controlling fires in their earliest stages—before flashover, before untenable conditions, and before tragedy.

At IFSA, we often say that fire sprinklers are not a modern invention—they are a time-tested life-safety technology. The lessons learned from the first Sprinkler Save still guide today’s codes, standards, and global efforts to expand the use of certified, properly designed water-based fire protection systems.

This anniversary is more than a historical milestone. It is a reminder that innovation, when grounded in purpose, can protect generations.

Have a Sprinkler Save to report? Help by submitting incidents through IFSA’s updated reporting portal. Save